‘Rebuilding has become a form of resistance, a way for Palestinians to express their own connections to this land and their right to a life here.’

EA Belinda

‘The trucks came in the middle of the night, about twenty of them,’ Aeed told us. They carried the building materials which the people of An Nabi Samwil needed to create a playground for the 50 or so children in the village. The trucks had to be brought in under the cover of darkness because it is illegal to build a playground or indeed anything at all in this village without a permit from the Israeli authorities, which are virtually impossible for Palestinians to obtain.

While Israeli development in occupied Palestine continues, the chances of Palestinians being granted permission to build are ‘slim to none’ (B’Tselem, Israeli human rights NGO). With no other options, many choose to build without permission. Their structures are considered illegal under Israeli law and risk being demolished by the Israeli authorities. The villages of An Nabi Samwil managed to lay the playground last year and to build a fence around it so that children could play football there without losing the ball down the slopes.

Aeed in front of the An Nabi Samwil playground

No freedom to build

The villagers added a surface of artificial grass to the playground this summer. Israeli soldiers told the village council in August that if they didn’t remove the artificial grass, the soldiers would come back to carry out many demolitions in the village, not just the playground. They could not challenge this in court as the order was oral and there was no formal, written demolition order. No-one doubted though that the military would carry out their threat – they had already demolished the women’s centre, which Aeed’s wife ran as well as part of the mosque. Nearly every family has received a demolition order at some point. Aeed alone has received 24 orders since 1996 of which 14 have been implemented.

No freedom to move

An Nabi Samwil is believed to be the site of the tomb of the prophet Samuel. It is the highest spot in Jerusalem, 1000 metres above sea level with stunning views in all directions. It used to take little more than ten minutes to travel to Damascus Gate, the central point of East Jerusalem, from here. Now, due to restrictions placed on Palestinian movement, it takes much longer, assuming residents can even get permission to go there.

The situation for An Nabi Samwil residents is complex. The village is on the Jerusalem side of the separation barrier, which Israel built to divide Jerusalem (which they consider to be part of Israel) and the occupied West Bank. However, the village was not included within the boundary when Israel expanded and illegally annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 war. Because of this, the residents of Ab Nawi Samwil are not eligible for Jerusalem residency cards and have West Bank residency cards instead. This means they cannot move freely around Jerusalem without permission, and risk stop-checks by Israeli soldiers.

However, due to the separation barrier and Israeli military guarded checkpoints, they cannot easily reach the West Bank either. They need permission from the Israeli authorities to receive visitors (even family members) with West Bank IDs or to receive deliveries. Living here has been described as like being confined to ‘an invisible cage’ (Al Haq, Palestinian human rights NGO).

Palestinian villages near to, or within Jerusalem are very vulnerable. The strict and bureaucratic ID card system applies to Palestinians only and not to Israeli residents. The complex residency system, lack of building opportunities and threats of demolition make it a real struggle for Palestinians to build a life here.

The residents built a playground (pictured above) for 150 children on another hilltop, this time at Jabal al Baba, and here they’ve managed to lay down an artificial grass covering as well as add a pair of goalposts and a baseball hoop. There is a large pole in the middle of the pitch but that doesn’t seem to bother anyone.

It was not easy to find a flat surface here on ‘Pope’s Mountain’, but they managed to make a playground in 2015, which the Israeli military later demolished. The community rebuilt it, but it was demolished again. This happened five times in all. One time they had to demolish it themselves – when the Israeli military carries out demolitions they often issue a bill to the residents for all their costs, so some families reluctantly choose the relatively cheaper option of demolishing the structure themselves to avoid this. The villagers rebuilt the playground again in 2016, this time on the part of the hilltop which belongs to the Vatican. The land had been a gift from the King of Jordan when the Pope visited it in 1964, before the Israeli occupation began.

Rebuilding has become a form of resistance, a way for Palestinians to express their own connections to this land and their right to a life here.

The village of Silwan is close to the centre of East Jerusalem and there is no spare land so the playground in the Batan al Hawa branch of the Madaa Centre (pictured above) is much smaller. It is built on the small courtyards of the building housing the centre. Silwan is a highly militarised area, with a large number of Israeli soldiers protecting the influx of religiously-conservative Israeli settlers who have moved here because they believe it to be the biblical site of King David.

The Madaa Centre is a Palestinian youth centre which was first established in 2007 in another part of Silwan, Wadi Hulweh. That centre has been demolished and then re-established, while its playground has become unsafe as a result of Israeli biblical archaeological excavations.

The Batan al Hawia centre is open every day and is free for all ages to attend but mainly caters for children from the age of five. About 100 children come every day and, as well as the usual type of children’s activities, there are talks by lawyers for children and their families. This may seem strange until you realise that ‘most children over ten or 11 will have been arrested’, the centre’s director told us. Most are accused of stone throwing, but he told of a case when a seven year old boy was arrested for shouting at a settler woman. He had shouted ‘God is most great’ in Arabic, a language she did not understand. The UN reported last year that since 2012 it had documented more than 560 cases of child detention in Silwan, including Batan al Hawa.

Tensions in Silwan are not uncommon. Whilst large numbers of Palestinians in the village face demolitions and eviction from the area, the number of Israeli settlers continues to grow, often through the takeover of Palestinian homes.

‘It is estimated that 199 Palestinian households currently have eviction cases filed against them, the majority initiated by settler organizations, placing 877 people, including 391 children, at risk of displacement.’

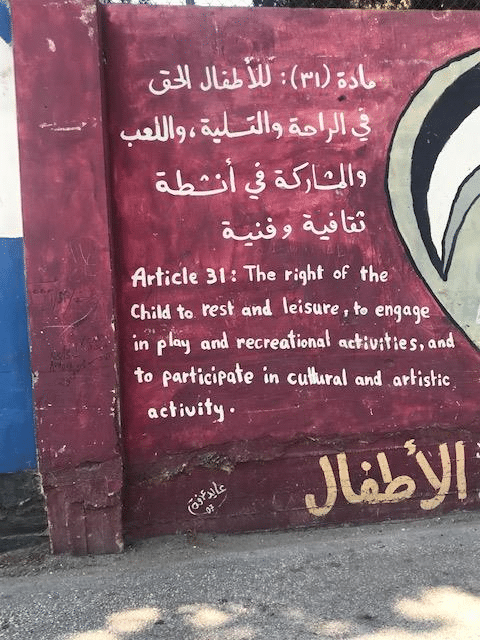

Graffiti on a wall outside Aida Refugee camp in Bethlehem