Jerusalem is one of the most iconic cities in the world. Most people picture the Old City, with its narrow streets, the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Western Wall. A visit here is, of course, a must for many tourists and pilgrims. However, Jerusalem is so much more than the religious sites of the Old City, and its future status will be critical to any negotiated peace settlement. In the eyes of the majority of the international community East Jerusalem, the Palestinian part of the city, is still part of the occupied West Bank, and will form the capital of any future Palestinian state.

Background

Following years of unrest, the United Nations drew up a ‘Partition Plan‘ in 1947 outlining its plan to divide the land between the Jewish and Palestinian populations. Jerusalem was to be exempt from the division, instead remaining as a unique, undivided city in recognition of its complex religious and demographic character. But the Partition Plan never came to fruition. In 1948, Israel unilaterally declared its independence and in the Arab-Israeli war that followed, some 75,000 Palestinians were forced to leave the Western part of Jerusalem, as 38 out of 40 villages were destroyed or depopulated.

By the end of the war, West Jerusalem was declared the capital of the new state of Israel with Palestinian East Jerusalem coming under the control of Jordan. This remained the status quo until the Six Day War in 1967 when Israel expanded its territory and began its occupation of East Jerusalem and the surrounding West Bank. In June 1980, Israel’s ‘Basic Law’ declared ‘East and West Jerusalem the United Capital of Israel’, effectively annexing the whole of Palestinian East Jerusalem, in contravention of international law. This move was rejected by UN Security Council Resolution 478 and has not been recognised by the majority of the international community, despite Donald Trump’s decision to move the US embassy there in May 2018.

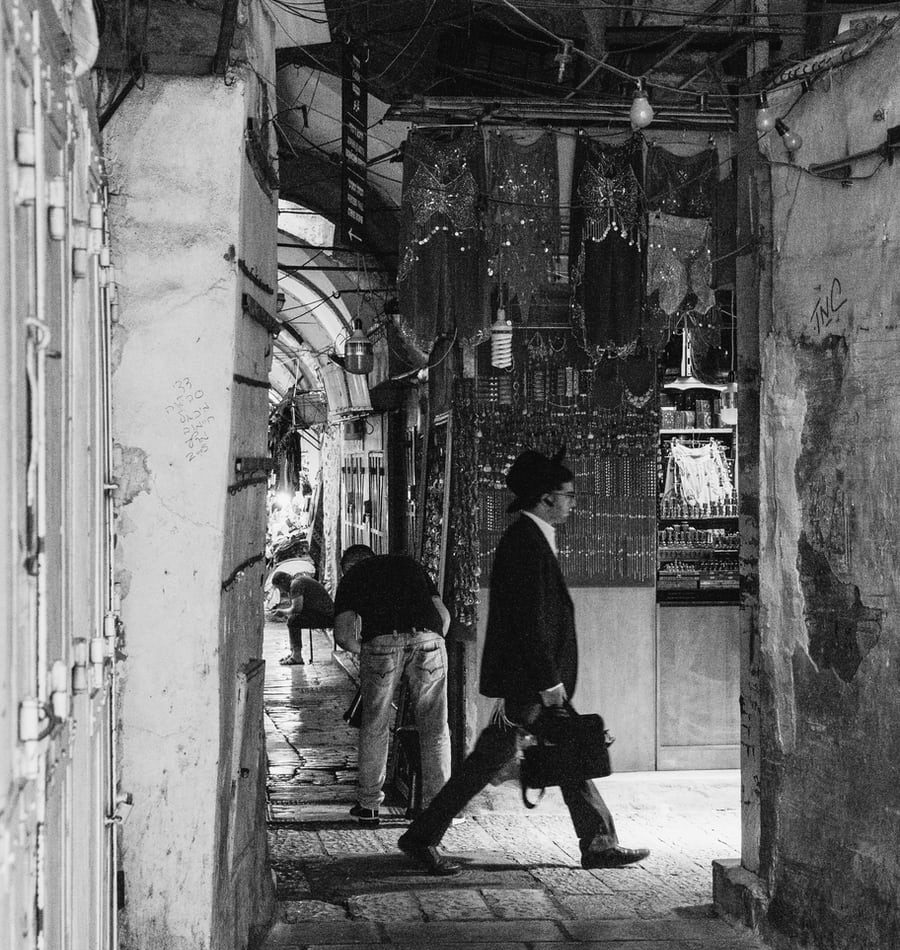

Today, the distinctively modern neighbourhoods of Israeli West Jerusalem are a marked contrast to the Palestinian neighbourhoods in the East. Palestinians in occupied East Jerusalem are required to pay taxes to the state of Israel like the residents of West Jerusalem, but do not receive the same services. In areas such as Silwan and Al Sawwiya, unkempt roads and concentrated housing provide evidence of the disparity in spending on services such as rubbish collection and highway maintenance.

‘Israel claims to treat Jerusalem as a unified city, but the reality is effectively one set of rules for Jews and another for Palestinians.’

The Israeli settlement of Ma’ale Adumim in the background, the Palestinian village of Jabal al Baba in foreground

Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem and the ‘Greater Jerusalem’ area

The annexation of East Jerusalem in 1980 paved the way for the building of illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied eastern part of city, with over 200,000 Israeli settlers now living there. Israel has also embarked on a project to expand its ‘Greater Jerusalem’ project deeper into the occupied West Bank with the establishment of new, large settlements such as Ma’ale Adumin (picture above). These well-planned and growing suburbs surrounding occupied East Jerusalem, with tens of thousands of settlers living in them, contrast sharply with Palestinian districts where it is extremely difficult to obtain planning permission from the Israeli authorities to build. To meet the needs of a growing population, many Palestinians choose to build without permission and live with the risk that their property will be demolished. From 2004 to the end of December 2018, Israeli authorities demolished 803 Palestinian housing units in East Jerusalem alone (B’Tselem).

‘Only some 15% of the land area in East Jerusalem (about 8.5% of Jerusalem’s municipal jurisdiction) is zoned for residential use by Palestinian residents, although Palestinians currently account for 40% of the city’s population.’

Settler organisations such Elad continue to bring pressure to ‘Judaize’ and settle East Jerusalem and the surrounding ‘Greater Jerusalem’ area, not least in ‘The City of David Park’ where archaeological excavations since 1967 have attempted to prove a Jewish historical link to a land which has been occupied by Arab Canaanites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and Muslims, as well as Jews. The state supports, and often funds, settler organisations which evict Palestinians from their homes in the city and replace them with Israeli settlers.

‘These settler enclaves have altered the neighborhoods in which they were established, making the lives of the Palestinian residents unbearable, the latter having to contend with legal proceedings aimed at driving them from their homes, invasion of their privacy, financial pressure and daily harassment.’

The rapid growth of settlements in and around East Jerusalem has also increased tensions and confrontations between Palestinians and settlers and brought with it an ‘increased presence of police, Border Police and state-paid private security personnel who use violence against the Palestinian residents, threaten them and arrest teens, thus exacerbating the disruption of life in the neighbourhood.’ (B’Tselem)

Residency Rights

Whilst all Jews in Jerusalem have full citizenship, Palestinians who were present in Jerusalem after 1967 were only given ‘residency status’ in the city. Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza cannot become residents of Palestinian East Jerusalem and must apply for permits from the state of Israel if they wish to visit, through a complex process described by Israeli human rights group, Machsom Watch, as a ‘bureaucratic maze‘. Even for those who have ‘residency’ this status does not afford the same rights as citizenship and maintaining residency is a challenge. Palestinians need to abide by a complex, bureaucratic system, continuously proving their right to live in the city. Since 1967, Israel has revoked the residency status of 14,595 Palestinians (Human Rights Watch).

‘Palestinians need to be able to show that the city is their “centre of life” by submitting dozens of documents including rent contracts, salary slips, electric and water bills as well as tax payments. Entrenched discrimination against Palestinians in East Jerusalem, including residency policies that imperil their legal status, feeds the alienation of the city’s residents’.

EA John